There are many unique and special records held within Stirling Council Archives. One such record is a Burgh Court Act Book known as the ‘Vagabond Book’. Dating from 1752-1787, the book is a good example of the crimes committed and operations of a Burgh Court in Scotland. It also provides a detailed insight into the kind of person who might otherwise would not have been recorded: the ‘vagabond’.

Those who had no abode and job were known as ‘vagabonds’ in the 18th Century, and as such are often written out of history. This can prove to be a barrier for many family historians. The ‘Vagabond Book’, however, does provide some basic genealogical information such as age, location, spouses, employment, parental information, and whether an individual was in work house.

The entries in the vagabond book record misdemeanours such as vagrancy, theft, breach of peace and assault. Moreover, it gives evidence of the actions and punishments the Bailies or Magistrates would serve to those convicted.

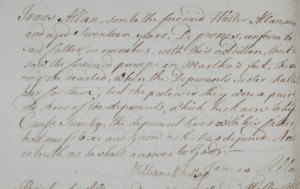

One of the first entries concerns the case of Martha Ferrier in December 1752. Ferrier had been in the poorhouse having previously been servant to Walter Allan, a hammerman in Stirling, from October of that year. He said that Martha had ‘provided a very bad service and was taken up with soldiers’. When Martha decided to abandon her service to Walter Allan, she was accused of stealing and wearing a pair of shoes as she fled the property. Walter Allan’s son, James, states that ‘he saw the foresaid pumps on Martha’s feet’ but that she ‘pretended they were a pair of old shoes’. No sentence was given and Martha returned to the poorhouse.

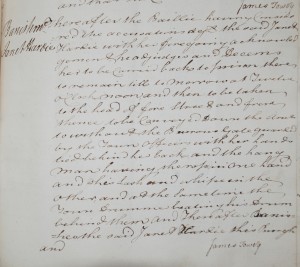

Repeat offenders in the town could be severely punished. Whipping and banishment from the Burgh of Stirling was common. On 4th July 1775, Janet Hardie was banished from the Burgh of Stirling for a second time because of disorderly behaviour. She was sentenced ‘to be taken to the head of fore street’ and then ‘conveyed down the streets to without the Burrows Gate guarded by the Town Officers with her hands tied behind her back, and the hangman having the rope in one hand and his lash and whip in the other, and at the same time the town Drummer beating his drum behind them’.

The Magistrates and Bailies of the Burgh could be lenient, if circumstances permitted. In July 1754, Margaret Ross was accused of disorderly behaviour, or more specifically drunkenness and throwing duds at her neighbours. She petitioned to be banished from Stirling if she was given ten to twelve days leave the town. Offenders often did this reduce the severity of their punishment. Ross, however, did not leave Stirling and re-offended again on the 11th June 1755, again accused of drunken behaviour.

The Magistrates decided that Margaret Ross would banished from the Burgh of Stirling forever. Conditions, however, were attached as she was said to have had ‘some small children’. If she was ever found within the Burgh again, Margaret would be ‘committed to a workhouse at hard labour for the space of three months and publikly wheep[e]d by the hands of the common hangman through the Burgh the first Friday of each month, and the last of these Fridays to be burnt on the face and again banished’.

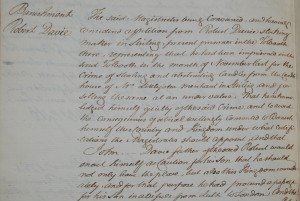

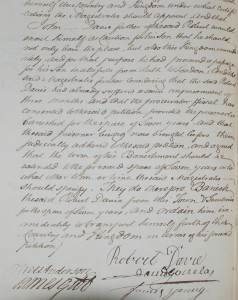

For those imprisoned, banishment from the Burgh of Stirling was often more appealing than life in the Tolbooth prison or the poorhouse. In 1786, Robert Davie, a stocking maker in Stirling, had been imprisoned in the Tolbooth for ‘stealing and abstracting candles from the candle house of Mrs Littlejohn, merchant in Stirling, and for selling the same at an undervalue’. Unusually, his father John Davie enacted a ‘caution for his son, that he should not only leave the place, but also this Kingdom immediately’. John Davie went even further and ‘procured a passage for his son in a vessel from Leith to London’. The Magistrates considered that because Robert had already served three months in the Tollbooth, they would agree to the petition if he was “banished for the space of 7 years’.