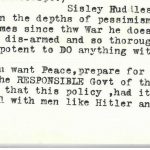

This entry focuses on British journalist and writer Sisley Huddleston who was critical of the actions of the government after World War One and advocated for the Pan-Europe manifesto presented by Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi. Graham describes Huddleston’s latest book as “very interesting, but in the depths of pessimism” in relation to British actions following the war. They both agree with the failures of the League of Nations and the unwillingness of those involved to modify the sanctions imposed on Germany, with Graham of the opinion that “much of our present predicament is due to the fact that they were not”.

Huddleston however, goes further to express the view in his works that the nation should have continued with its disarmament programme as “if you want Peace, prepare for Peace”. From previous thoughts shared in his diary, we know Graham to be strongly against this idea and conversely felt that the government should have begun to rearm the nation a long time ago. He ponders “is that (preparing for peace) really a practical hypothesis for the RESPONSIBLE Govt of this country? Is there one ray of hope that this policy, had it been thorougjly(sic) adopted, would have weighed at all with men like Hitler and Von Ribbentrop, or with Mussolini?”

Having the luxury of hindsight, we know that Graham was unfortunately correct in his analysis of the situation at the time and that pacifying Nazi Germany more than had already occurred would not have halted Hitler’s aggressive expansionist intentions. On the 22nd of May, mere days before this latest diary entry, the military and political “Pact of Steel” alliance between Germany and Italy was signed. Whilst this openly declared a continuing relationship of co-operation between the two, there were also secret aspects to the pact, that focused on quickly strengthening their military and economic ties, which we now know came to bear huge consequences as the conflict developed.

For his part during the war, Huddleston was based in Vichy France where he took French citizenship, interviewed Marshal Philippe Petain and expressed sympathy towards the Vichy regime. For these actions, he was considered to have committed treason and was arrested in 1944 and imprisoned for being a collaborator. He continued with his journalism throughout this period, and was in particular critical of the way the Allies approached liberating France.

Graham goes on to discuss the element of revenge playing a large part in the current situation and highlights what in his opinion, is a “hatred” between France and Germany. Having had significant sanctions stipulated to them following World War One, many Germans felt that not only had they lost the war, but were unfairly blamed entirely for the conflict. Losing territory, military strength and the ability to properly recover in the face of huge reparations bills and later also against the backdrop of The Depression, facilitated the conditions for the Nazi party and their rhetoric to gain dominance in the political and social spheres. Although a sweeping generalisation to say that all Germans wanted “revenge”, it is certainly accurate to suggest as Graham has in his closing statement that “their present leaders undoubtedly” (did), and that this was a factor in their subsequent actions.

Sources used:

www.wikipedia.com

www.britannica.com

www.awm.gov.au