To coincide with the Stirling Libraries Off The Page Book Festival, we are making a blog post for each day of the Festival to showcase records held at the Council Archives that fit in with the themes that the Festival is exploring this year.

For our first post, we take a look at early Tourism in Scotland. Starting in the eighteenth century, when Scottish people, particularly of the upper classes, were starting to have more leisure time, and the political situation had become calmer, resulting in safer conditions in which to enjoy the exploration of the beautiful countryside that this nation is justly famous for.

The Romantics and Royalty

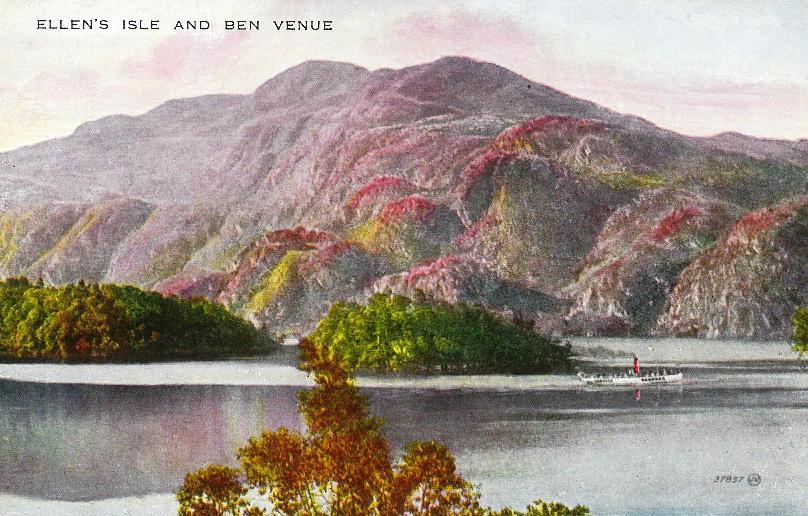

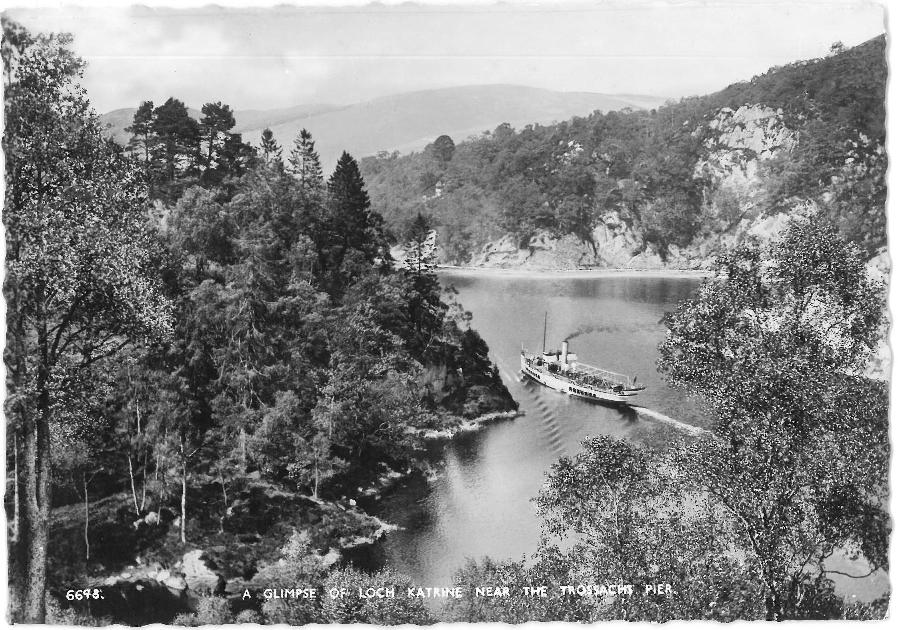

In a very real sense, tourism in Scotland as we think of it today, started in the Trossachs area. Picturesque enough to give a ‘wild’ flavour to any excursion, yet easily accessible from Edinburgh and Glasgow, the beautiful countryside of the Trossachs area has been a magnet to visitors since the late eighteenth century.

The first ‘tourist guide’ for the area was Thomas Pennant’s Tour of Scotland published in 1769, which included a very favourable review for the Trossachs. This contributed to the popularisation of the area, although initially, it was only the very wealthy who could afford to visit.

The development of the Romantic Movement in art and literature in the later eighteenth century coincided in Scotland with a period of relative stability and financial security after the upheaval associated with the mid-century Jacobite rebellion. One of the features of Romanticism was an appreciation of the beauty of wild nature, known as ‘the cult of the picturesque’. Romantic poets such as William and Dorothy Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge visited Scotland in the early nineteenth century, walked in the countryside, appreciating its beauty and going home to write about it, attracting other like-minded people to come and see what had inspired them so.

Walter Scott’s narrative poem The Lady of the Lake, published in 1810, and featuring action set around Loch Katrine, further boosted the popularity of the area. The poem proved to be extremely popular and encouraged hundreds of tourists to sign-up for excursions to visit the Loch and the countryside around it. There is a reason why the current pleasure boat on the Loch is called the Sir Walter Scott.

Scott was also heavily influential in one of the other early nineteenth century occasions that popularised Scotland as a tourist destination at this time. No British King had made a visit to Scotland since 1651, when Charles II came to Edinburgh for his Scottish Coronation. In 1822, the recently crowned King George IV decided that a Royal visit to Scotland was long overdue. This was part of a general campaign to make the unpopular monarch more palatable to his subjects. George was viewed as hedonistic and autocratic and had received some bad press owing to his treatment of his estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick, around 1821. There had also been anti-establishment uprisings in Central Scotland at this time that were brutally suppressed leaving a legacy of unease and resentment against the Crown and Government of the time across the area. The aim of the visit was to soothe ruffled feelings and establish George as a legitimate King of Scotland, who had taken the Scottish crown legitimately, by his right of succession.

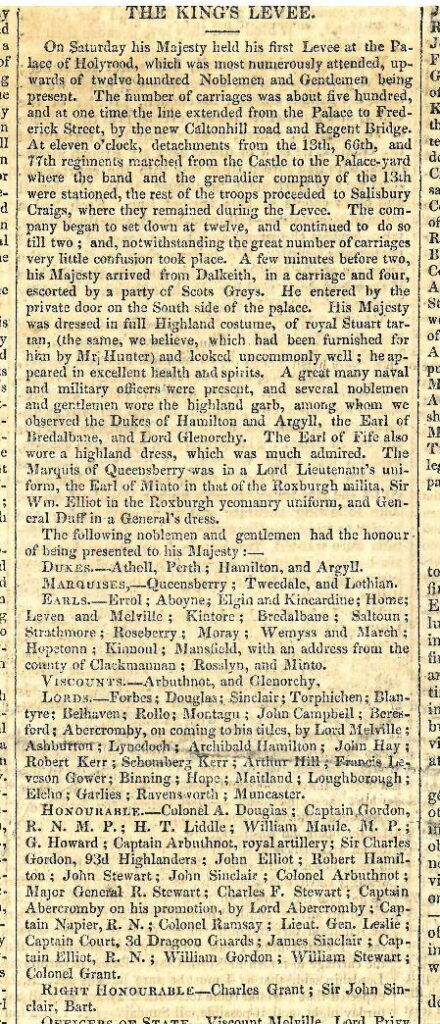

When the King decided on his visit to his Scottish subjects, he engaged the celebrated writer, Sir Walter Scott, to advise him on how he might display himself to his best advantage, and to organise the various events that were to take place during his stay. Scott had become acquainted with George back when he was still Prince Regent, and was granted a baronetcy by the King after his accession to the throne in 1820. Scott envisaged a celebration that was uniquely Scottish in character, and roped the Clan Chieftains and most of the notable Scots families into his planning. Instructions were distributed to the citizens of Edinburgh as to what clothing it might be best to wear on the streets during the Royal visit, which took place between the 14th and the 30th of August 1822. For the Highland Ball held on the first Saturday of the visit, all gentlemen who were not in uniform were instructed by Sir Walter to wear ‘the ancient Highland costume’. Scott also encouraged George to emphasise his right to the Scottish throne as a legitimate heir of the Stuart line, and as a result of consultation with the writer, the King placed an order with George Hunter & Co. of London and Edinburgh for a full outfit in the bright red tartan that later came to be called Royal Stuart. It was in this rather startling ensemble that the King appeared at the Ball. A portrait of George in his costume was painted by the prominent Scottish portraitist David Wilkie, who flattered the King by toning down the brightness of his plaid, lengthening the skirt of the kilt, and leaving out the pink tights that George wore to cover his legs. In actuality, the kilt was unusually short, falling well above the Royal knees, resulting in a number of unflattering caricatures appearing in the press not long after the event.

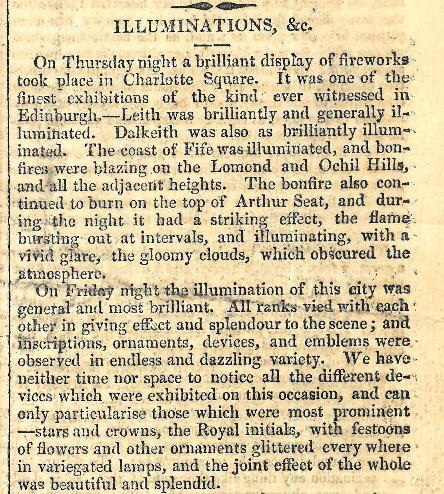

Ultimately, the visit was declared a resounding success. The carefully organised events were all packed-out, and crowds lined the streets to cheer the King as he went to his various engagements. Representatives from all of Scotland’s fashionable and noble families attended the balls and levees, and a good time appeared to have been had by all at the end of proceedings even if some local people were somewhat bemused by the whole experience. John Murray, the Fourth Duke of Athol referred to the event in his diary as ‘one and twenty daft days’. After the enthusiasm that accompanied the parades and balls and general festivities that were held, and the generally approving coverage in the newspapers of the time, more and more people were attracted to Scotland as a travel destination.

You can read more about the occasion, including the pink tights that King George wore with his kilt here.

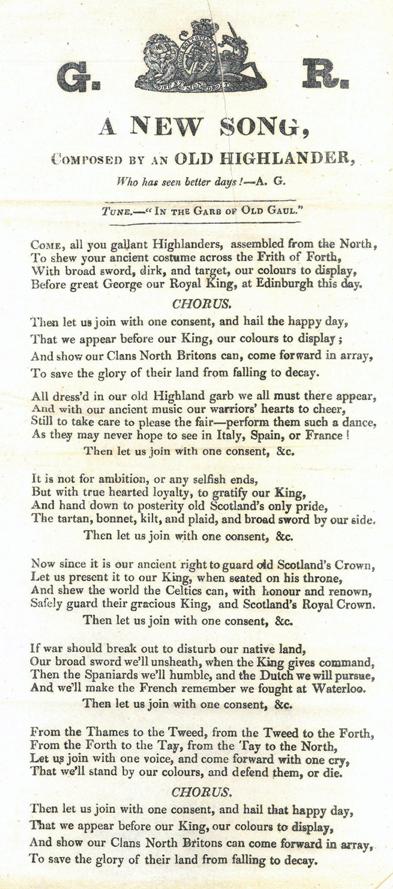

The Archives holds a poem that was written for this occasion as part of the papers of the Clan McGreor. Sir Evan McGregor, the Clan Chieftain at the time, along with other Clan members, were given the honour of guarding the Scottish Royal Regalia during the pageantry surrounding the King’s visit in 1822.

The song mentions the wearing of ‘our old Highland garb’. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that this event re-popularised the wearing of both the small kilt (Feileadh-beag) and the full belted plaid (Feileadh-mhor) as Scotland’s national dress, after a period in which they had gone into abeyance as day to day clothing after the proscriptions of the Dress Act, which had only been repealed in 1782.

The enthusiasm of Queen Victoria for Scotland also contributed to the rise in tourist numbers later in the nineteenth century. The Queen was known for her love of Scotland, and she holidayed here regularly, making the areas that she was particularly fond of popular destinations for fashionable people from the mid-century onwards.

Clan Gatherings – the Rise of Historical Tourism

Along with the rising popularity of Scotland as a tourist destination for the sake of its beautiful scenery, came another type of tourist – the amateur historian and genealogist. Clan Gatherings became more generally popular from the early part of the nineteenth century onwards. The Clan Gregor papers in the Council Archives include a lot of information about the organisation of such assemblies, and it is clear from this source that the attendance at such gatherings began to include people of the Scottish diaspora from all over the world from this time.

Gatherings of the Clan Gregor often included short excursions to sites that had particular significance in the history of the Clan, so that attendees could see the areas and settlements where their ancestors lived and places of specific interest, such as Rob Roy McGregor’s grave at Balquhidder.

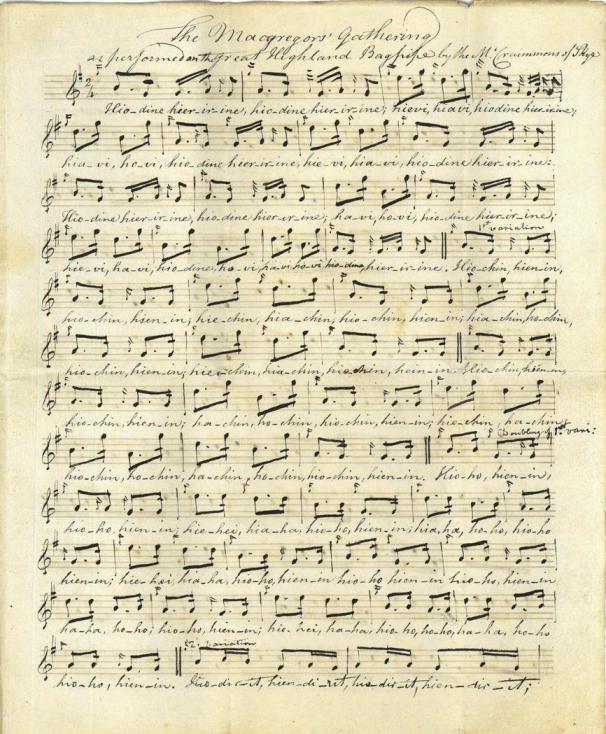

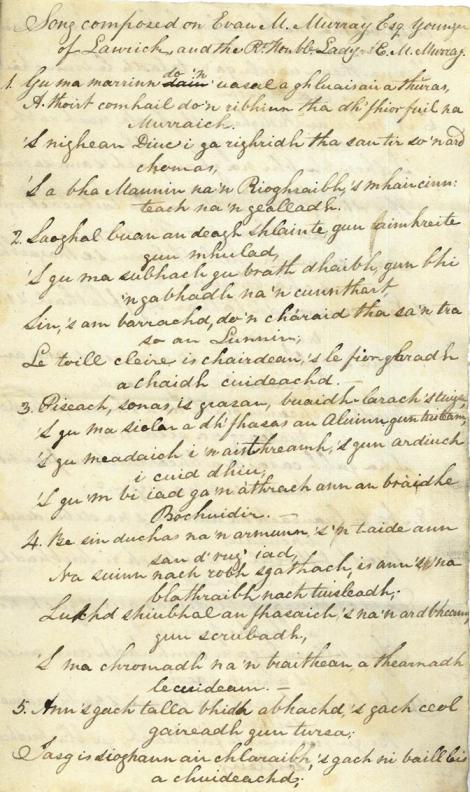

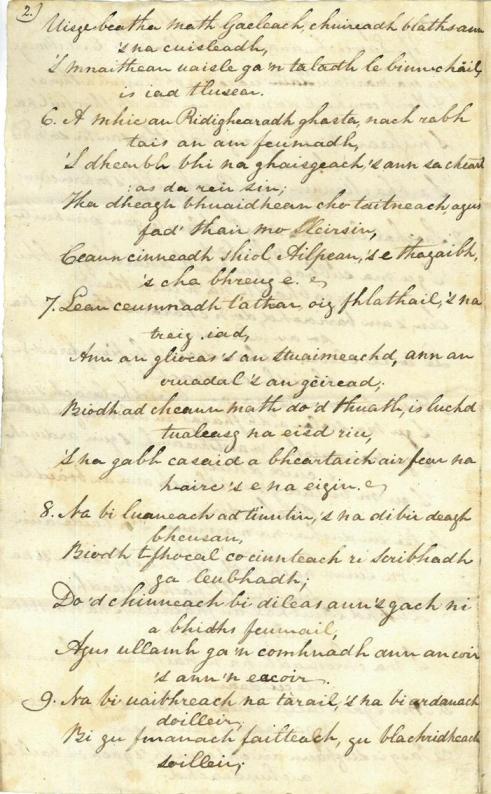

The gatherings were also cultural occasions that featured dancing, singing and the recitation of poetry. There are some lovely examples of original works in the archives of the Clan. These include a song that was specially written for the Clan Gathering of 1816 as well as pipe music and a song written in the Gaelic by John McGregor for his wife.

If you have a comment or question about the information given in this post, or simply want to make an enquiry to the Archives, please email us at: –