There is a small bundle of documents held at the Archives of letters and accounts relating to the arrangements made for the execution of two men who many at the time believed died as martyrs in the cause of freedom. The Burgh Town Clerk’s Office under the Clerk Alexander Littlejohn were given the task of organising the execution, which was to happen at Stirling Castle on the 8th of September. The documents, with their matter of fact discussion of the technicalities of the sentence of hanging and then decapitation, make for particularly gruesome reading.

By 1820, reformist fervour was high in Scotland. Radical ideas had remained in abeyance through the period of the Napoleonic wars. However, after the end of the conflict in 1815, Britain experienced an economic downturn that served to generate renewed interest in reform. In the first decade of the 19th century, the average wage of a weaver in Scotland was halved and continued to fall after this. Weavers, particularly in Scotland, were skilled craftsmen, literate, informed and radical in their outlook. In 1813, in protest at their reduced standard of living, 40,000 weavers went on strike for over two months, a dispute that only ended when the government arrested the leaders of their union and forced the men back to work. News of the slaughter of radical protesters demonstrating in Manchester in 1819, an event that came to be known as the Peterloo Massacre, caused consternation amongst reformists across Britain. Meanwhile, concern was also growing within the Establishment at increasing demands for reform from workers in many occupations. With the horrors of the French revolution very much in mind, the Government was nervous of potential dissent and prepared to employ its spies and agents provocateurs to quash any revolutionary activities amongst the populace. This was the background to the events of 1820.

Rumours of unrest amongst the population in the Stirling area were already circulating in the early part of the year. A letter was written to William Murray of Polmaise and Touchadam, a prominent local landowner whose family papers are held at Stirling Council Archives, on the 26th February by Alexander Jenkin, a Nailmaker in St Ninians warning of potential insurrection:

“…a very alarming circumstance which seems to be at hand & it is at the risk of my life if this is known which I hope you will conciel. The spirit of Rebellion has rained so much in owr 3 United Kingdoms that they have carried on the business in secret by Delegats from every quarter… the first day of March is the day…for the 3 Kingdoms to rise in mass and overthro Government…”

In Glasgow, the local unions had formed a covert ‘Committee For Organising a Provisional Government’ and this Committee was organising opposition to the government and using ex-soldiers such as John Baird, a weaver from Condorrat, to train willing men how to fight. Government spies had already infiltrated this movement by 1820 and a meeting of the Committee at Marshall’s Tavern, Gallowgate, Glasgow, on the 21st March was betrayed to the authorities by one John King, a weaver from Anderston. The Committee was surprised, arrested and detained in secret. So successful was this move that none of the radical associates of the men involved were aware of what had happened.

It is widely agreed by historians that the uprising that followed this was engineered by the authorities to encourage those who were prepared to respond to a call to arms to show themselves so that they could be apprehended and dealt with. The men who instigated the organisation of the events of April 1820, John King, a weaver, Duncan Turner, a tinsmith and Robert Lees, known as ‘The Englishman’ are now regarded as having been working for the government; although they were instrumental in the organisation of what happened, they disappeared after the event and were not tried for their part in it. There is no doubt that the unrest throughout Scotland and the north of England at this time issued from real grievances and a desire for change, it was as a response to these that the authorities sought to entrap men such as Baird and Hardie and this sealed their fate.

On the 22nd March, King, Turner and Lees attended a meeting of radicals in Glasgow and reported that a large-scale uprising was about to happen. On the 23rd March, in Glasgow, Duncan Turner revealed plans to establish a provisional government. He also produced a draft proclamation to be posted around the city calling for radicals to refuse to work and to consider rebellion and the establishment of a new regime. The posters duly appeared on the 1st of April. The response was immediate and alarming for the government. Huge numbers of workers in central Scotland went on strike on the 3rd April. There were widespread reports of men banding together and making weapons. Men were seen drilling on Glasgow Green and locally, there was an assembly of around 200 men gathered at Balfron to discuss what should be done to further their cause. Another letter written to William Murray of Polmaise by John Fraser, one of his tenants, spoke of men making pikes in St Ninians:

“A boy last night was disturbed in the act of stealing different articles from soldiers in the Castle, and while under confinement in the Guard room amused himself with drawing the figures of pikes which he said people were making at St Ninians.”

On the 4th of April, Duncan Turner mustered a small group of men at Germiston and persuaded them to march on the Carron ironworks where they were to take the building and provide themselves with more weapons from the stores there. Citing that he had organising work to do elsewhere, Turner passed leadership of the group to Andrew Hardie, a young weaver from Glasgow. Hardie was given a torn card to be matched with that held by another supporter whom he would meet at Condorrat. This man was John Baird, weaver there who was given his half of the card by John King. More men were to be mustered along the way until they had a force capable of storming the works. The two men met and showed their cards at Condorrat at 5 am on the morning of 5th April. Although Baird was disappointed at the small number of men that arrived with Hardie, having been told by King to expect an army, the 30 men continued on through the early morning towards Falkirk. Meanwhile, 16 Hussars and 16 of the local Yeomanry forces had been warned of the approach of the radicals and were mobilised to meet them at Carron. The two groups met at Bonnymuir where King had told the rebels to wait while he went to fetch reinforcements from Camelon. Shots were exchanged and there was a short skirmish that ended when the soldiers charged the small band of rebels and overpowered them. Some of the men were able to escape, but 19 were apprehended and taken as prisoners to Stirling Castle.

Despite the fact that there were further disturbances at Strathaven, East Kilbride, Paisley and Greenock between the 5th and 8th of April, this was effectively the end of the uprising.

In all, 88 men were charged with treason as a result of the uprising but only three paid the ultimate penalty. Special Royal Commissions of Oyer and Terminer were set up at Glasgow to hear the cases. James Wilson was tried at Glasgow on the 29th July and found guilty of one of the charges of treason against him. He was hanged and beheaded in Glasgow on 30th August. 20,000 people turned out to see the spectacle, many of these his supporters.

Andrew Hardie and John Baird were tried on the 4th August. At the trial the Judge advised “To you Andrew Hardie and John Baird I can hold out little or no hope of mercy… as you were the leaders, I am afraid that example must be given by you.” They were accordingly sentenced to death for their views and beliefs, betrayed by the establishment that they had sought to reform. The rest of the rebels were sentenced to be transported overseas to penal colonies in New South Wales and Tasmania.

Public execution in Stirling was usually handled by the Hangman or Staffman as he was known. This official had his own acre at Braehead and a house on St John’s Street. Previously, in the 17th century, executions had taken place at the Mailing Gallows where the black Boy Fountain now stands. On this occasion however, such was the public feeling for the two condemned men that officials were brought in secret from Glasgow to Stirling to undertake their grisly work. Two men were required, one hangman and one decapitator. The latter gentleman had precise requirements with regard to what equipment should be available to him on the day. All were to be brought to Stirling from Glasgow, secretly and at night. There is even a memo detailing the best way of dealing with the decapitation. The letters give details of the need for secrecy:

“The man [the Decapitator] wishes of all things to be kept private so that it must be gone about as quietly as possible, so that nobody may know when he comes and goes…” Galbraith to Littlejohn 2nd September 1820.

“Meantime as the Person [the Hangman]… wishes to remain incog. and to be conducted from here by a confidential person who will be able to land him secretly at some place of secrecy & security which you can fix on and point out…” George Salmond to Littlejohn 2nd September 1820.

Baird and Hardie were executed on the 8th September at Stirling, a crowd of 2,000 people were in attendance. Brave to the last, both men gave short speeches on the scaffold, Baird ended his speech “Although this day we die an ignominious death by unjust laws our blood, which in a very few minutes shall flow on this scaffold, will cry to heaven for vengeance, and may it be the means of our afflicted Countrymen’s speedy redemption.” Hardie then spoke of “our blood, shed on this scaffold… for no other sin but seeking the legitimate rights of our ill-used and down trodden beloved Countrymen”, then when the Sheriff angrily intervened he concluded by asking those present to “go quietly home and read your Bibles, and remember the fate of Hardie and Baird.” They were then hanged and after a while on the scaffold, cut down to be beheaded by the decapitator. The following description of the execution was written by local Surgeon Thomas Lucas whose diaries are held at the Council Archives: -.

“The Executions of Baird and Hardy took place before the Broad Stair of the Town House between the hours of Two and three pm. They were drawn on a Hurdle from the Castle to the place of Execution guarded by a strong Guard of horse and foot and attended by the three established Clergy. They both addressed the Spectators and declared that they were Murdered for the cause of Justice truth and Liberty. The Crowd shouted out Murder. After hanging 35 minutes a fellow in disguise severed their heads from their bodies in a very bungling and awkward manner by severall strokes with an axe to each of them. The Hangman, headsman, Hurdleman, Hurdle and the horse were all from Glasgow. Their Corpses were put into Coffins and carried into the Prison and about 9 o’clock the same evening they were interred in the Churchyard, and a Military guard placed over their graves, to prevent their relations from lifting their bodies, in order to bury them in their own parishes.”

Both officials were gowned and masked so that their identity could not be seen by the crowd. The robe worn and axe used by the decapitator can be seen in The Smith Museum and Art Gallery today.

The last letter in the bundle is from Thomas Young, the Hangman and is dated 13th November 1820.

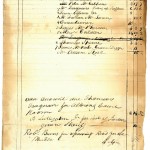

In it he complains that he has still not been paid in full for his work. As may be seen from the account of the expenses of the execution, presented by the Town Clerk of Stirling to the Treasury for payment, his was the highest fee at £40.