For this month’s ‘Document of the Month’ feature, and in time for International Women’s Day in March, we are featuring a determined women, her protest and the subsequent impact that she had on the policy for the treatment of women by the local police force.

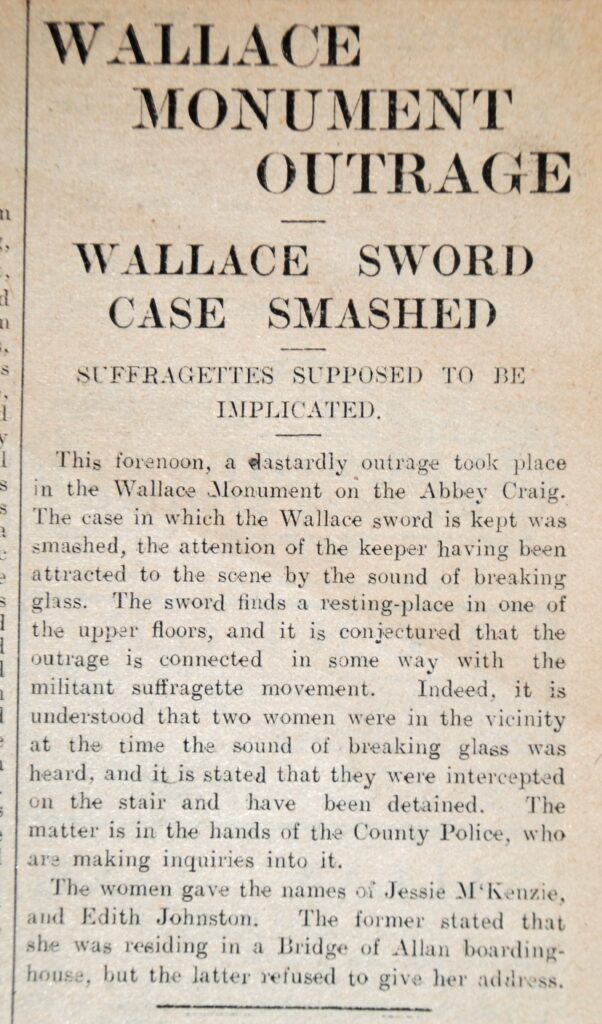

On Thursday the 29th August 1912, a woman visiting the Wallace Monument smashed the glass case housing the Wallace Sword with a stone. She placed a note into the broken case alongside the stone and hastened away to her accomplice, who was just outside the room. Both women were arrested shortly afterwards. The Stirling Journal reported the incident that day as it went to press quite late in the afternoon.

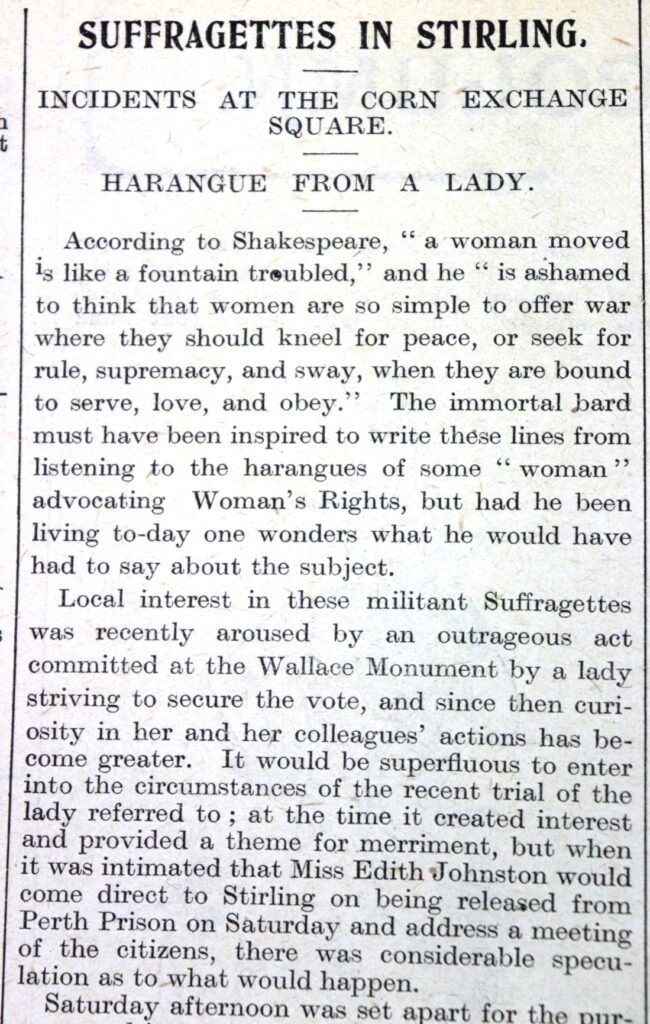

The Stirling Observer featured a long article with all the details of the incident in its Tuesday edition the following week:

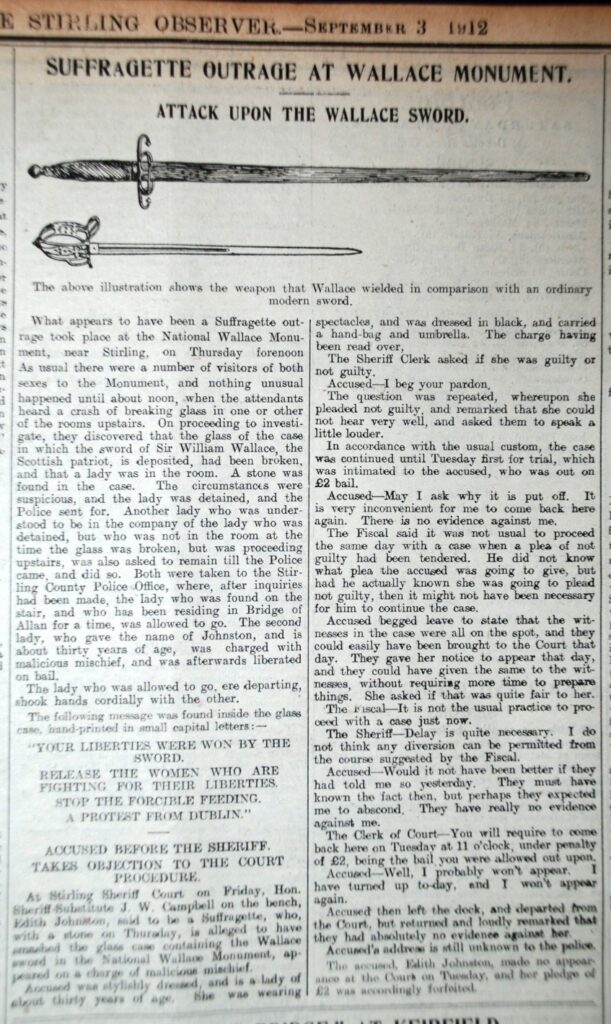

Stirling Observer 3rd September 1912

““…nothing unusual happened until about noon, when the attendants heard the crash of breaking glass…on proceeding to investigate, they discovered that the glass of the case in which the sword of Sir William Wallace, the Scottish patriot, is deposited, had been broken and that a lady was in the room. A stone was found in the case. The circumstances were suspicious and the lady was detained, and the Police sent for. Another lady who was understood to be in the company of the lady who was detained, but who was not in the room at the time the glass was broken, but was proceeding upstairs, was also asked to remain until the Police came, and did so. Both were taken to the Stirling County Police Office, where, after enquiries had been made, the lady who was found on the stair, and who has been residing in Bridge of Allan for a time, was allowed to go. The second lady, who gave the name of Johnston, and is about thirty years of age, was charged with malicious mischief, and was afterwards liberated on bail.

The following message was found inside the glass case, hand printed in small capital letters: –

YOUR LIBERTIES WERE WON BY THE SWORD. RELEASE THE WOMEN WHO ARE FIGHTING FOR THEIR LIBERTIES. STOP THE FORCIBLE FEEDING. A PROTEST FROM DUBLIN.”

‘Edith Johnstone’ was, in fact, Ethel Moorhead, a well-known Suffragette who was living in Edinburgh. Her companion was a contact living in Bridge of Allan, and the action had been planned meticulously as a protest to gain publicity for the cause of women’s suffrage. The article continued:

At Stirling Sheriff Court on Friday, Hon Sheriff-Substitute J.W. Campbell on the bench, Edith Johnston, said to be a Suffragette, who with a stone on Thursday, is alleged to have smashed the glass case containing the Wallace Sword in the National Wallace Monument, appeared on a charge of malicious mischief.

Ethel pleaded ‘not guilty’ and the case was adjourned until the following Tuesday ‘in accordance with the usual custom’.

Edith: ‘May I ask why it is put off? It is very inconvenient for me to come back here again. There is no evidence against me.’

The accused begged leave to state that the witnesses in the case were all on the spot, and they could easily have been brought to the court that day. They gave her notice to appear that day and they could have given the same to the witnesses, without requiring more time to prepare things. She asked if that was quite fair to her.

‘Edith’ was told that the delay was ‘quite necessary’

She is then quoted as saying: ‘Would it not have been better if they had told me so yesterday. They must have known the fact then, but perhaps they expected me to abscond. They really have no evidence against me.’

The Clerk of Court responded: ‘You will require to come back here on Tuesday at 11 o’clock, under penalty of £2, being the bail you were allowed out upon.’

‘Edith’ is quoted again ‘Well, I probably won’t appear. I have turned up today, and I won’t appear again.’

The accused, Edith Johnston, made no appearance at the court on Tuesday.

Of course all of this was done to ensure that Ethel would be brought before the court again and that the general interest around her trial would be keen, the idea being to gain a public platform from which Ethel could make a statement about the campaign for women’s suffrage. Ethel was arrested on the evening of Friday 6th September at her home in Edinburgh and brought to Stirling where she spent the night in one of the cells at Stirling Sheriff Court. More about this later.

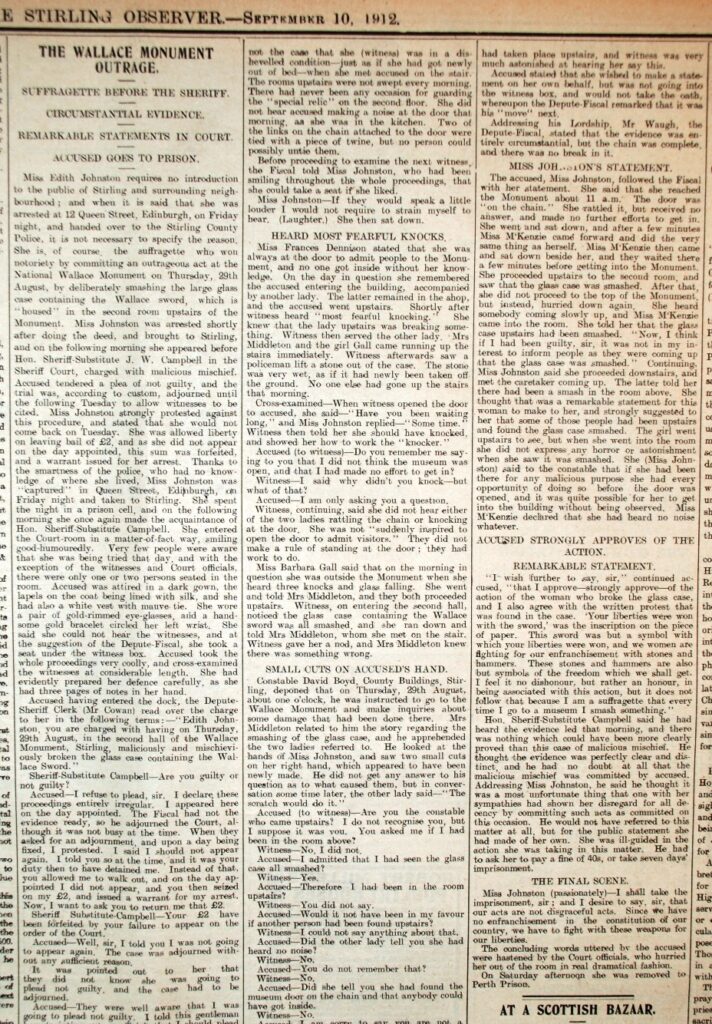

The trial was convened on the morning of Saturday 7th September, and received full coverage in the Stirling Observer of the following Tuesday. Ethel insisted that there was no evidence against her and demanded that she be released:

Stirling Observer, 10th September 1912

Ethel: ‘I refuse to plead, Sir. I declare these proceedings entirely irregular. I appeared here on the day appointed. The Fiscal had not the evidence ready, so he adjourned the Court, although it was not busy at the time. When they asked for an adjournment, and upon a day being fixed, I protested. I said I should not appear again. I told you so at the time, and it was your duty then to have detained me. Instead of that, you allowed me to walk out, and on the day appointed I did not appear, and you then seized on my £2 and issued a warrant for my arrest. Now I want to ask you to return me that £2.

The aim was clearly to make as much fuss as possible, and by doing so gain additional publicity for the campaign for women’s suffrage. At the end of the trial Ethel gave a statement in which she drew parallels between the cause for which William Wallace fought, and the cause for which she herself was fighting:

I wish further to say sir that I approve – strongly approve – of the action of the woman that broke the glass case, and I also agree with the written protest that was found in the case. ‘Your liberties were won with the sword’ was the inscription on the piece of paper. This sword was but a symbol with which your liberties were won, and we women are fighting for our enfranchisement with stones and hammers. These stones and hammers are also but symbols of the freedom which we shall get. I feel it no dishonour, but rather an honour, in being associated with this action, but it does not follow that because I am a Suffragette that every time I go to a museum I smash something.

Despite her insistence that there was no evidence that she had committed the offence, Ethel was found guilty, as she doubtless knew she would be, and as she was not prepared to pay the fine, she was sentenced to a week in Perth Prison, where she was taken directly after the trial.

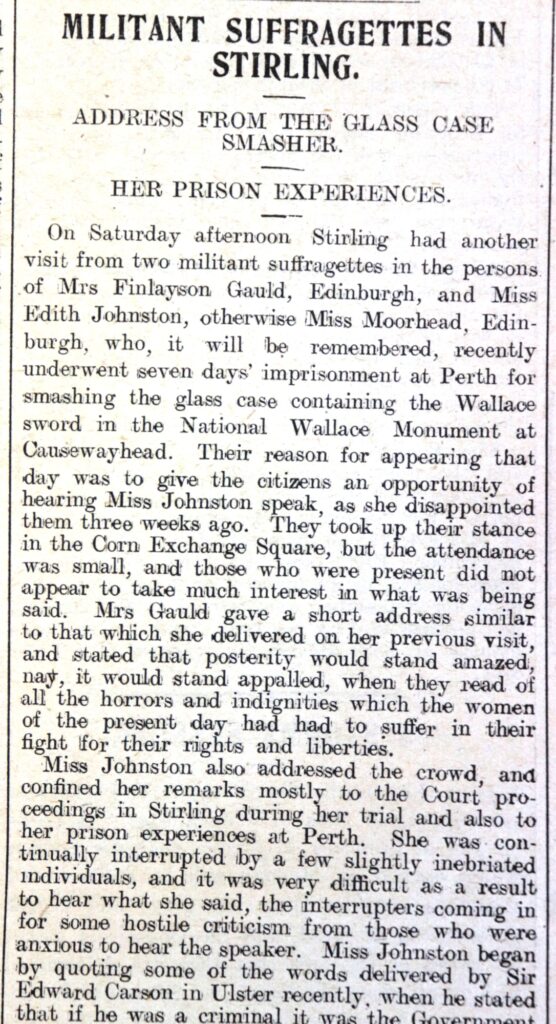

Once Ethel was freed, she came back to Stirling twice in the company of other Suffragettes to attend public meetings, once on the 17th September, when she did not speak, and again on the 12th October when she did give a short address.

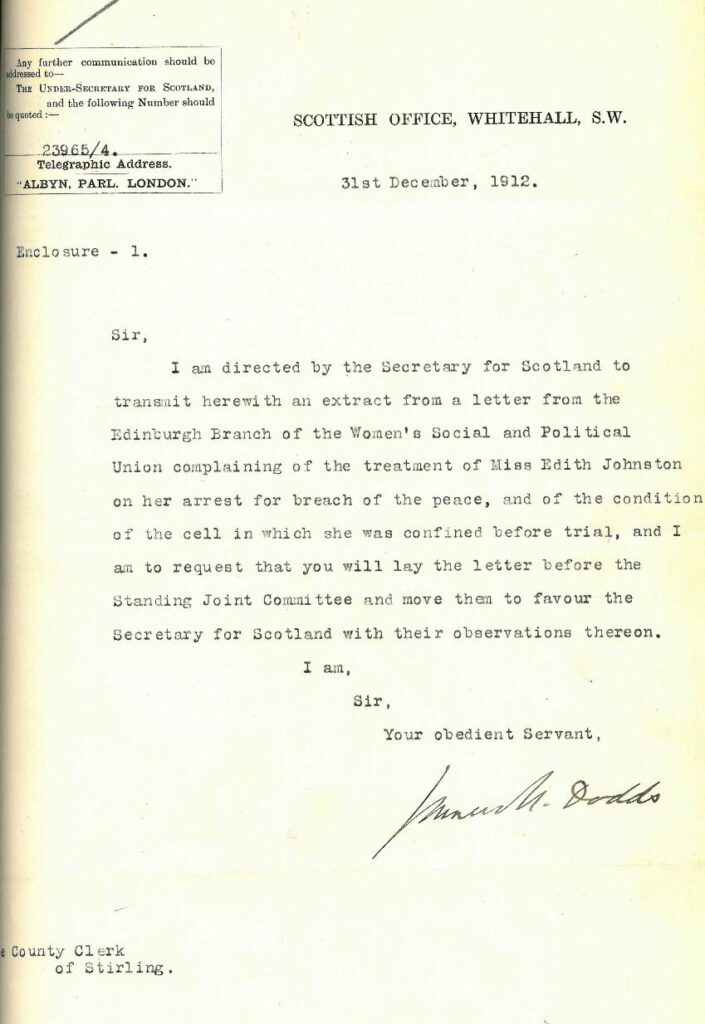

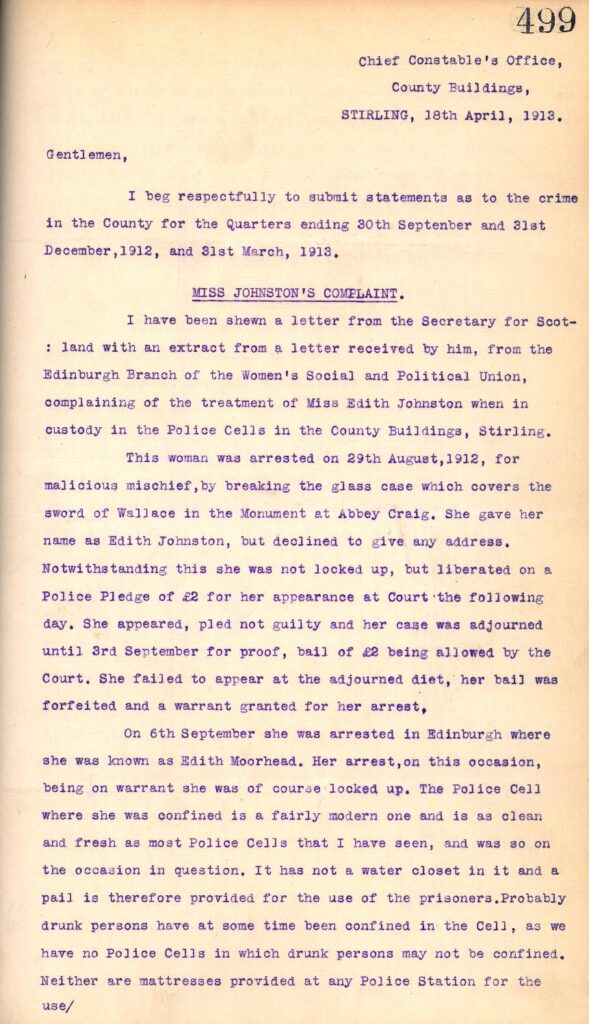

Ethel’s influence on local affairs did not stop there, however. After her release from prison, she saw to it that a complaint was sent to the Scottish Office by the Edinburgh Branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union about the state of the cells in Stirling Sheriff Court and the treatment that Ethel received when she stayed there. This complaint was passed by the Scottish Office to the Clerk of Stirlingshire County Council with a direction that the response was to be relayed to the Secretary of State for Scotland:

The recent practice of the Police in Scotland is to refuse bail to Suffragettes and to imprison them in ‘drunk cells’ at the Police Station, where they are kept all night. There is no sleeping accommodation in these cells and male warders come in and out during the night. On the 6th of September, Miss Edith Johnston was arrested and taken to Stirling and imprisoned for the night in a “drunk cell” at the Police Station. No mattress was provided for the wooden bed, and there was a foul smell in this cell. We request that you will have an enquiry made into this treatment of the Suffragettes…

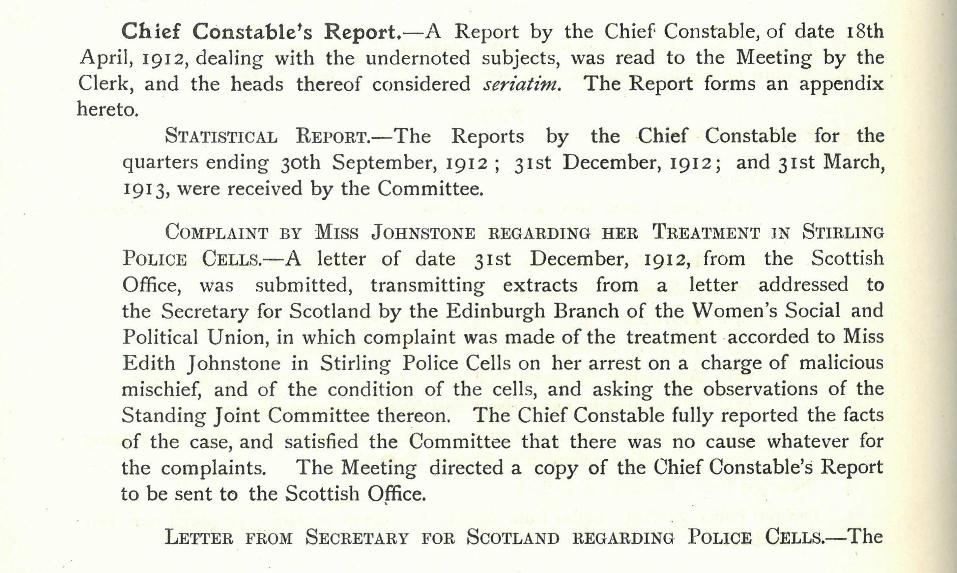

The County Council directed that the Chief Constable of Stirlingshire compile a report on the matter. Given the interest taken by the Scottish Office, the report produced was very comprehensive. A minute of the County Council meeting of 18th April 1913 gives a good summary of the findings:

The Chief Constable fully reported the facts of the case, and satisfied the Committee that there was no cause whatever for the complaints.

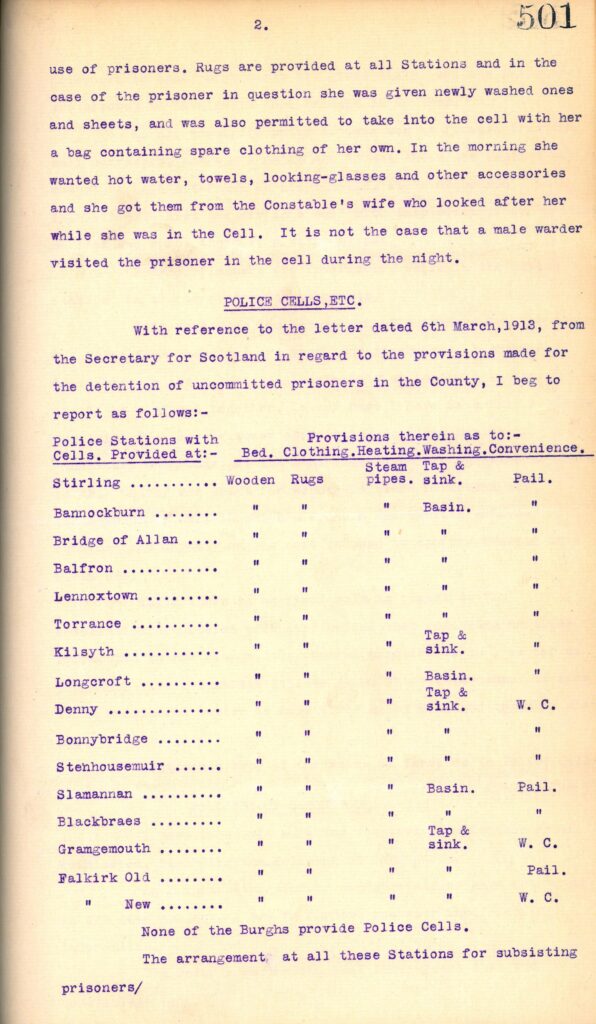

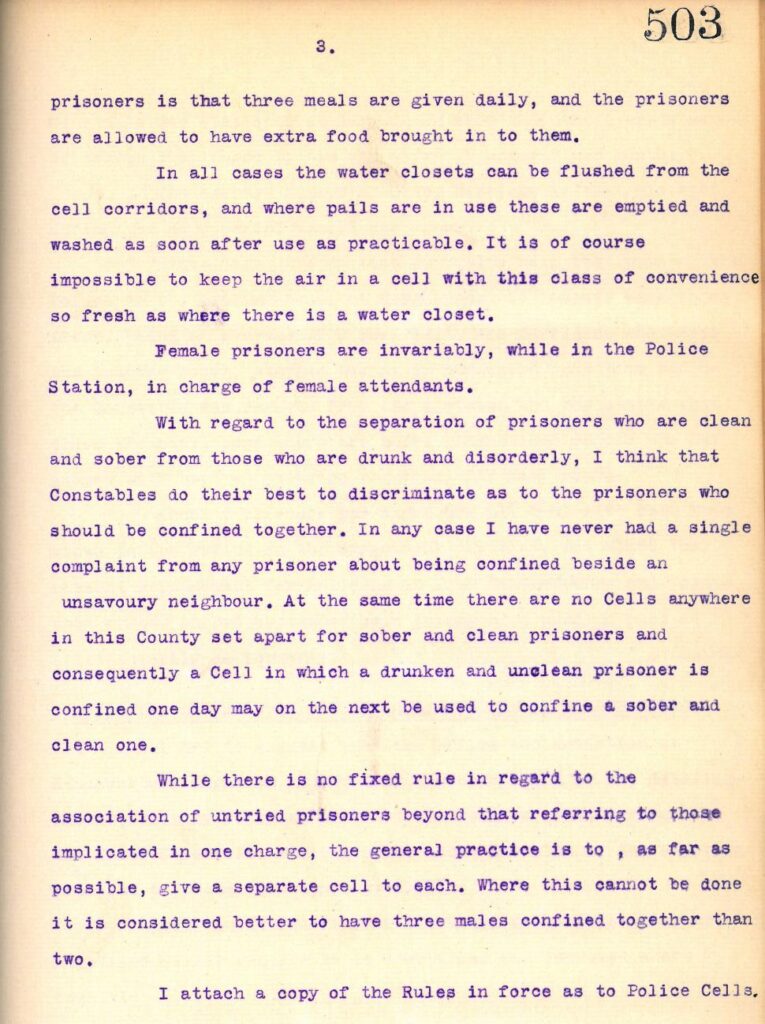

The Scottish Office requested a full report about conditions in Police cells in Stirling generally as a result of the complaint by Ethel: –

…letter of date 6th March 1913 from the Scottish Office, asking for a full report on the various Police Cells in the County, with special reference to sleeping accommodation, provision of bedding rugs, washing facilities, provision of food, heating arrangements, sanitary conveniences and attendance on female prisoners by female attendants, as also the association in the same cell of tried and untried prisoners…The Committee were of opinion that the state of matters disclosed by the report was on the whole satisfactory, but that it would be desirable if moveable beds could be fitted in all the cells.

The report also gave details of Ethel’s night in the cells:

The Police cell where she was confined is a fairly modern one and is as clean and fresh as most Police cells that I have seen…it has not a water closet in it…neither are mattresses provided at any Police Station for the use of prisoners. Rugs are provided at all stations and in the case of the prisoner in question she was given newly washed ones and sheets… In the morning she wanted hot water, towels, looking glasses and other accessories and she got them from the Constable’s wife who looked after her while she was in the Cell. It is not the case that a male warder visited the prisoner in the cell during the night.

It is amusing imagining an imperious Ethel demanding various things be brought to her cell and a flustered Constable on duty making sure that she got everything she wanted.

Ethel Moorhead made her mark on Stirling in 1912. Not only through her protest, which gave her a platform to make her argument about women’s right to enfranchisement, but also through her complaint about her treatment as a prisoner in the Sheriff Court, a complaint that resulted in a change of policy, and subsequently, the treatment of women in police custody right across the county.